1. Attempting to write a critical text solely with bibliographic references found in the Pivô Art Research library

It couldn’t be any different. I, as the author, proposed to use the same working substrate as Pedro Zylbersztajn: to write this small critical text based on the books and materials present in the Pivô library. Since I started as the curator of the institution in 2022, I have witnessed changes regarding the use of the space: its inauguration as a reading and research place specialized in visual arts and its opening to the general public; institutional (and personal) negotiations for the consolidation of the collection; Pivô Recebe events, a project in which the library transformed into a cinema, a stage for lectures and performances, or a space for book launches; and the project itself, a known (but undisclosed) number of rumors spread through the pages of a circulating library, to which I will dedicate myself in the following paragraphs. The most interesting aspect of this library space has always been, to me, its versatility.

When approached by Pedro Zylbersztajn at the end of 2021 to carry out a project in this place, I was excited, considering that the artist already had a previous relationship with the institution – he was a resident at Pivô Pesquisa – and a study on the world of archives, memory spaces, and places where information and knowledge infrastructures are concentrated. That library has always been, to me, a space to be made, and the artist’s proposal fit into the coefficient of indeterminacy given to those experimental places.

Pedro suggested almost a second residency in the library: he offered to spend time observing the social space and existing protocols within that place and, based on them, conceive a project that would emerge from that experience and spread in a decentralized manner, like a rumor – for months on end, we even called the project Rumor. For me, one dimension of the event and the artist’s desire to create, from the library’s pre-existing conditions, a system of information circulation without defined control, allowing information to move freely, transforming and dissipating over time, was clear from the beginning. From the start, there was a possibility that the project would be a narrative: something that had been seen and witnessed by a group of people.

2. The Ghost and the Retiree

For months, Zylbersztajn dedicated hours to observing the cataloging system, shelf organization, and titles that composed the library’s collection. Additionally, he witnessed the constant organization and reorganization processes of the space to accommodate the events I referred to earlier. When asked, the artist described his presence throughout the year at Pivô as that of a ghost, or a retiree: both move through space unnoticed and, at the same time, possess what is most valuable in human life – time. Zylbersztajn devoted himself to randomly flipping through books and compiling images that would serve as the basis for his work in drawing and text. The arrangements of words, images, and drawings resulting from this investigative process are what we began to call rumors. To describe them, we borrow the artist’s own words: “The elements that compose each rumor are defined from a vast research process in the collection, from which selected images, fragments of texts, and ideas are derived, whose meanings connect unstably through different arrangements”.

The rumors were conceived to inhabit the space between the pages of books. And, as they took shape, they requested both witnesses of their existence and accomplices in their diffusion among the books. Therefore, three moments were thought of in which the project gained public dimension: in the first of them, lasting only one day, the small arrangements of paper were distributed in the library space in an exhibition composed of shelves, tables, and other furniture emptied of books and displaced from their original orientation. Sculptural supports for rumors were created, and those present were invited to participate in a kind of ritual: the movement of rumors from the installative supports into the books. For the second and third moments, events and dialogues were proposed in which people who were somehow present in the library were invited, such as authors, editors, organizers, or artists whose works were shown in their books.

In the first moment, the rumors coexisted (or we could even think that they summoned) with a performance by artist Nolan Oswald Dennis, a South African artist with whom Zylbersztajn has collaborated in recent years. The event consisted of inviting a group of people to read together, for the first time, a text based on the history of the Mapungubwe Complex in South Africa. As a starting point, Dennis proposes what he calls reverse archaeology, that is, a refusal to treat the past as a resource to be extracted (from the earth). And, in a second and final moment, the artist invited Flora Leite, Jandir Jr., Maira Dietrich, and Paulo Pasta to choose other volumes that are part of the collection and present to the public some kind of comment – of any nature – about them.

Held in the context of a known (but undisclosed) number of rumors spread through the pages of a circulating library, the last two activities were fundamental for the propagation of rumors and, at the same time, brought to light debates related to the library space as an information infrastructure and repository of knowledge: what data should be considered when proposing a library archaeology? Perhaps, in addition to the books themselves, acquisition policies, the very land on which Pivô is installed, and the portion of space chosen to house the books were still at play. When we first hear about the rumors, are we compelled to spread the word about their existence? Is there a potential for refusal inscribed in each statement and secret? How to make visible the rumors, silent dialogues, and chains of influence that come into existence when books inhabit the same space?

3. What the rumors tell

After being stored in that sort of performance or farewell ceremony, the rumors entered a state of rest: they await to be stumbled upon by an unsuspecting reader, who seeks, in the library, the materiality of verbal things, or by someone who obstinately searches for them among the publications.

We know that there are readers for whom books exist while they are being read and later are only memories of the pages, and they feel they are dispensable in their physical incarnations. Others, however, fill books with their own rumors and feel compelled to scribble, deface, or annotate—even those objects that belong to public collections. In this sense, there is an imminent possibility of encounters between the silent rumors conceived by Zylbersztajn and others who may eventually have the books in their hands.

As I write this text, I have dedicated myself to reading some works by Alberto Manguel about libraries. I read this author during college, and sometimes in relation to Jorge Luis Borges, with whom he lived for years. In one of his latest books published in Brazil, “Packing My Library,” the Argentine narrates his house move and, simultaneously, traces a brief history of libraries that were conceived as large receptacles of human knowledge and arrives at one of the maxims that help me understand my compulsion with books and also the world of collecting in general: “To collect is to exert control over what is unbearable.” The author goes so far as to assert that publications are testaments to the impossibility of fully conveying what our experience apprehends, and furthermore, a potential audience for enunciation composed of a

“silent majority” that can be mobilized whenever the reader wishes.

By adding these small rumors to the library’s books, Zylbersztajn adds probable statements to this great discursive chain of voices. What might be the possible responses of readers to these inquiries and notes inscribed in the rumors? The books themselves, by living with such insertions, in a cover-to-cover and page-to-page dialogue, wouldn’t they also whisper inaudible answers, at first glance, to the library visitor?

The texts that integrate and tie each arrangement of rumors are documentary microfictions. Written by Zylbersztajn, they do not strictly fit into the category of truth or lie, but focus on the universe of archives, documentation, and cataloging of memory, as well as everyday existence in spaces. The texts cover a variety of topics, from simple observations of elements that exist in the library to events that occur during reading or in the institution itself. Furthermore, they may include delusions that depart from a hyperbolic reality, speeding up everyday events to their limits, making them impossible, fictional, or abstract. The texts deal with the apparatuses and behaviors of those who frequent the library space – human or non-human. By conceiving the rumors and receiving them among its books, the library, often seen as a stronghold of silence, is evidenced as an environment in which meanings interconnect among the shelves. The arrangement of books reflects this dialogue between them and with the readers.

4. The grand archive for the rumors

To write this text, I circled both in my personal library and in those where the rumors currently inhabit: I found editions of common books or publications that seem intrusive within a logical, but somewhat arbitrary organization system. This simple attentive look at the book spines elicited a series of memories in me about the moment when the books were acquired or read. While conducting this exercise, I remembered – and identified with – the way Manguel describes his library: “A flock of pages that held the key to my past and instructions for my present, as well as useful amulets for everyday rituals.”

In my wanderings among shelves and bookcases, I came across the book “The Big Archive: Art from Bureaucracy” by Sven Spieker, acquired some years ago when I set out to develop a research project on archives and contemporary art. The author identifies the typewriter, index cards, papers, and cards as archive technologies. He explains: to the bureaucrat, archives contain little more than rubbish, documents that are no longer necessary; to the historian, on the other hand, the archive’s content represents an almost objective corollary of the “living” past; whereas 20th-century art used the archive in various ways – from what the author calls Marcel Duchamp’s “anemic archive” of ready-mades and El Lissitzky’s Demonstrative Rooms to post-war artists’ compilations of photographs, such as Susan Hiller and Gerhard Richter. In the book, Spieker proposes to investigate the archive both as a bureaucratic institution and as something akin to a laboratory of experiments on the nature of vision and its relationship with contingent time. Archives, in the field of arts, are altered in response to changes in media technologies – the typewriter, telephone, telegraph, film – and, according to the author, are responsible for forging a specific visuality for the relationship with time.

Right in the book’s introduction, Spieker makes an interesting digression from Andy Warhol’s time capsule works and states: “Archives do not record so much the experience as its absence: they mark the point where an experience is absent from its proper place, and what is returned to us in an archive may well be something we never possessed in the first place. There is a part of an archive that escapes the control of the archivist, beyond the archive.” In the realization of the installation at Pivô, perhaps Zylbersztajn’s role was that of an archivist and cataloger within the library space. Perhaps the work was driven by the desire to create something that existed on the threshold of invisibility and visibility – a space so commonly inhabited by some printed copies, which are listed in databases and often go years without being seen or handled. With tireless dedication to monographs and theoretical books on the artistic field, he managed to inhabit the seemingly empty spaces between the pages and, in a way, proposed to engage in dialogue with them. Only the artist knows many of the secrets and erasures

Inscribed in these places, such that the rumors highlight and serve as an archive of these.

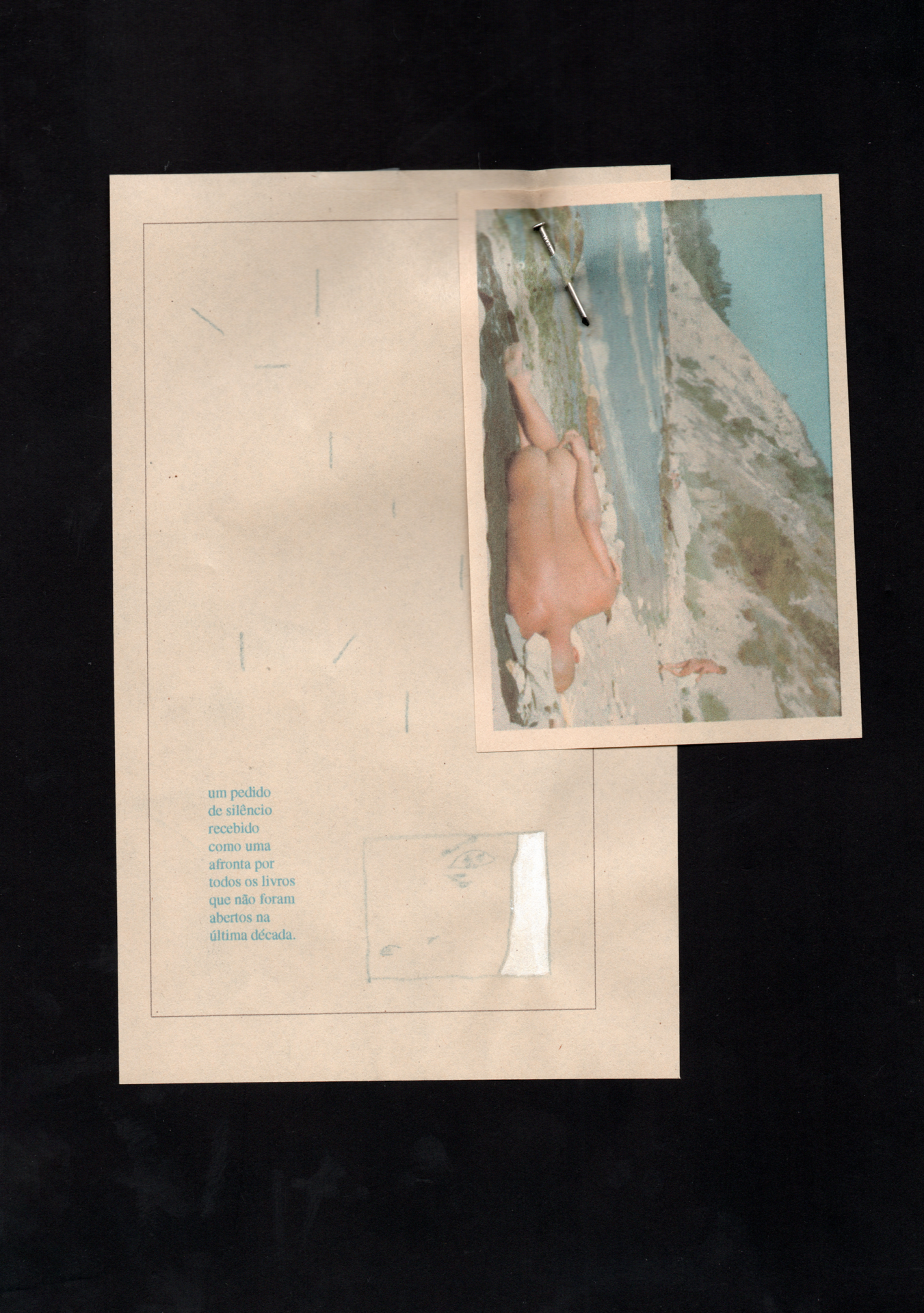

As we encounter the arrangements of text, image, and drawings, as described earlier, we navigate through a series of small narratives about the librarian (perhaps literary) universe and the personal lives of those who coexist in the library space. Among them, there is no clear marking of time: the narrated events could be contemporary to us or have occurred in the distant past. There is a certain ephemeral architecture in the composition of the rumors themselves, realized with the use of paper clips and other tools for the momentary joining of elements: the very precariousness of the support and drawing materials (newspaper paper, carbon paper), which go against the instinct of preserving the archive and, in a sense, need to be hidden inside the books, out of sight most of the time, to continue existing.

We could assert that the installation, like the rumors, has an uncertain duration, as it depends on the books in the collection moving through the gestures of the readers. I would venture to say that the work a known (yet undisclosed) number of rumors spread across the pages of a circulating library is a reflection on time – of words, texts, and the significance of images – and the resonance of murmurs emanating from humans and non-humans who coexist among the books.

Português

Português