As the opening of her show at Pivo, In Vivo, is postponed until further notice, artist Caroline Mesquita and curator Dorothée Dupuis discuss The Ballad, a movie and installation produced in 2017, which embody many ways of thinking and making of the artist. The film The Ballad will exceptionally be available here until May 24.

Dorothée Dupuis: In order to let spectators know a little more about your work before they are able to discover your exhibition at Pivo when the space can reopen, we talked about showing older projects of yours and we decided to show The Ballad (2017), a film and an installation which were produced for two individual exhibitions at the Ricard Foundation in Paris in 2017 and then at 221A in Vancouver, both curated by Martha Kirszenbaum. Could you first tell us about the title, The Ballad?

Caroline Mesquita: In French, a “ballade” is a short piece of music or poetry, whereas a “balade” (which pronounces the same) is also a stroll, going out for a walk. The film was then conceived as a ramble between several coloured, abstract environments, populated by a gallery of very different characters but all played by me, who are the characters of an aeroplane: passengers, pilot, hostess, mechanic… But also, the idea of wandering, it is also a reference to how I built this project at the time, it has been an organic work process where one thing led to another… I also liked the idea that a ballad is a lighthearted song, there was this idea of a trippy, surreal installation… even if I realize that we could have put many other words on this project.

DD: Speaking of The Ballad as a musical term, could you tell us about the sound in this video and maybe also in your videos in particular? What you are looking for, how you work.

CM: Sound in my practice is a metaphor for this quest to extend my medium and the capacities of my objects at all costs, not to stop at finite forms – like when at the beginning of my practice, I made prints on paper or fabric with the oxidation of brass and copper. I quickly started making sounds with sculptures, like Drums (2014) that we had shown together at PSM in Berlin with Petunia, which was an agglomeration of different volumes in steel, an instrument disguised as sculpture, which had produced the sounds of the surrounding soundtrack. I also made flutes, with tubes from other sculptures, and then I started to use each of my sculptures as a potential source of “sounds”. The idea is that the sculptures can become different things, sound, videos, I don’t fetishize them too much: in the films we see the sculptures getting painted, falling, scratching each other. Metal has this ability to transform, it can be cut, merged: I always think of the example of sculptures that were founded during the war to make cannons. It reflects this quest for a changing identity, which is also present in the film. In The Ballad, I make the metal characters speak, react, the sound comes from manipulating them, making them clink, it is produced through their bodies, like noises coming from them, a kind of language. Just as their colouring comes from oxidation, as if they were sweating: I try to get the most out of them, literally. In the soundtrack we also hear voices, the clarinet – I used to play it when I was little – the flutes, the drums, and also the sculpture I made at Fahrenheit in Los Angeles which served as a gigantic instrument. It is a sculptural sound universe, which accompanies the abstract paintings that are the decorations in painting that we see in the film: an expressive abstract environment filled with vibrations. That was my goal.

DD: The Ballad is, therefore, the story of an aeroplane crash and its victims. The video tells the interaction between these survivors, who are all played by you in different costumes, and a group of your rolled brass sculptures, halfway between an erotic and cannibalistic story (the sculptures hurt the characters as much as they caress them). In an interview in Numéro during the Ricard exhibition, you said that you were fascinated by the stories of plane disappearances. Similarly, in several of your other videos, there is an accident or event that kills or makes your characters unconscious. What fascinates you about the idea of the disaster?

CM: Well, it is not so much the figure of the crash that fascinates me, like that of the disappearance – like that of the plane in the Little Prince of Saint Exupéry – and the unknown story that can happen next. Eroticism and violence, these are things that we can actually interpret from video, but it is before all an encounter between the sculptures and these human organisms: they touch them, are curious about this material, try to see what is inside, like children who ingeniously discover something. The crash was also a way to make my characters inert. Besides, they are not all survivors, some are probably dead. In my first videos, like Some blue in my mouth (2016), I built my characters as a sculptor, then in the next video it is the sculptures themselves that manipulate me, that’s why disaster situations, accidents, it was a way to stage all that. In The Visitors (2018), the film which follows The Ballad, they are just sleeping characters, dozing in a house, a garden: also a narrative trick to make the human body inert. In The Ballad, I’m the one who plays all the characters. At that time, it was important for me to change my identity, I wanted to transform myself, the video also spoke of the ability to reinvent yourself, to escape from a form of social or other destiny. This freedom to reimagine myself was a crucial question at that time in my practice, this is also why I have created many works inspired by motorized machines, motorcycles, planes, rockets, for their ability to make me travel, escape.

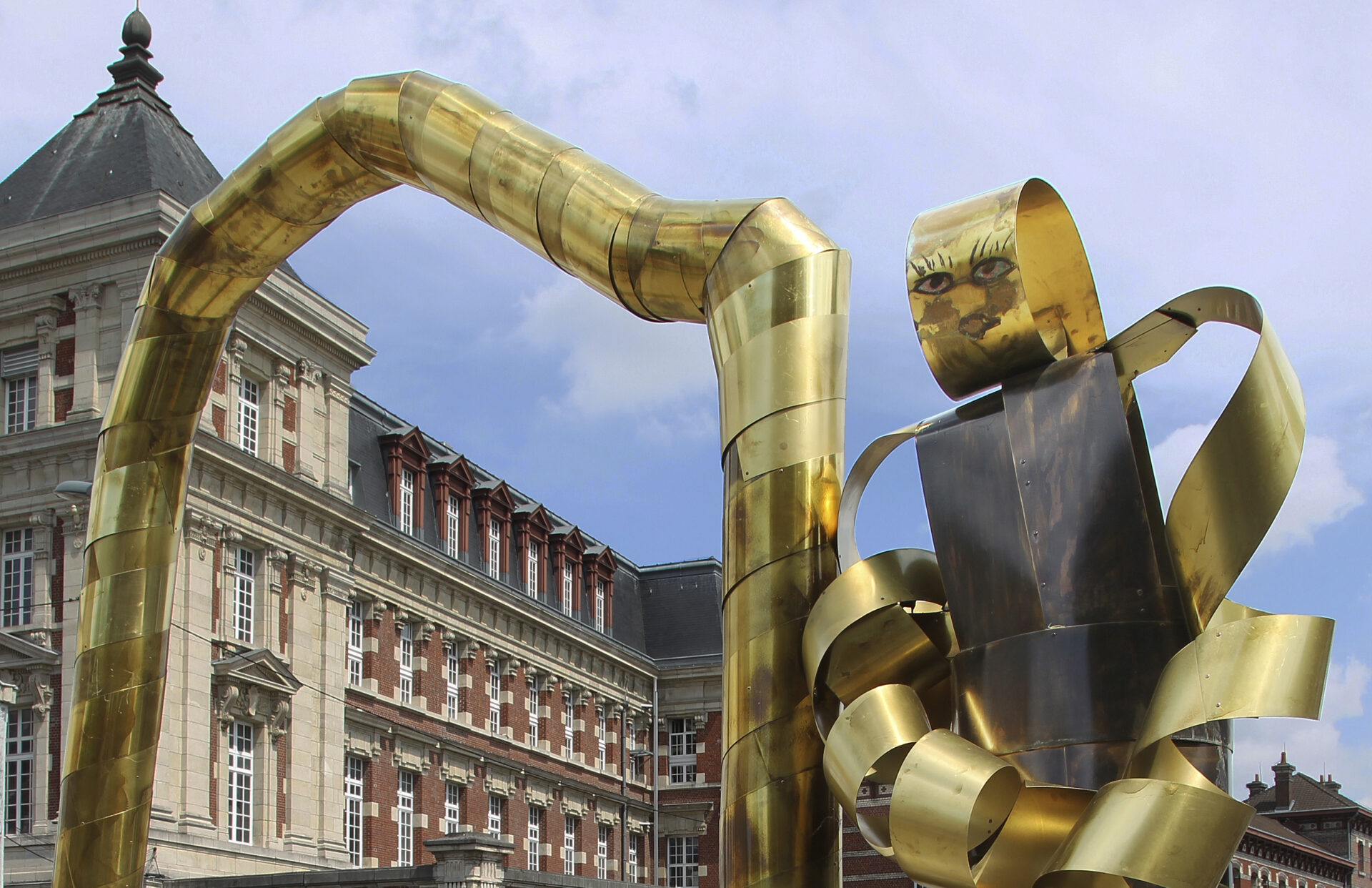

DD: Precisely, The Ballad was an opportunity for us to collaborate again last year since I proposed to you to present this work again as part of a monumental collective exhibition, La Déesse Verte, that I designed at the invitation of the Lille 3000 Festival. The Green Goddess was an opportunity to address issues that have intersected my curatorial practice for several years, such as feminism, the relationship with the environment, both natural and constructed, inter-species relationships, our relationships with non-European civilizations, among others. The figure of the jungle as a metaphor for the unknown and possible site of encounter between different beings, aliens or others, was present and therefore the plane crash of The Ballad was a major figure at the end of the exhibition, composing an apocalyptic landscape in semi-darkness, a way of talking about the end of the world but far from the too theoretical discourse, rather calling on the imagination and fantasy of the viewer. You also created a gigantic character at the entrance of the exhibition location, adjoining a sort of cosmic “door” inspired by other science fiction stories like the Stargate series for example. Is science fiction a source of inspiration for you? Do you see artists as sort of prophets capable of predicting certain future situations with their works, or simply painters interpreting reality and the present? Where do you feel more comfortable?

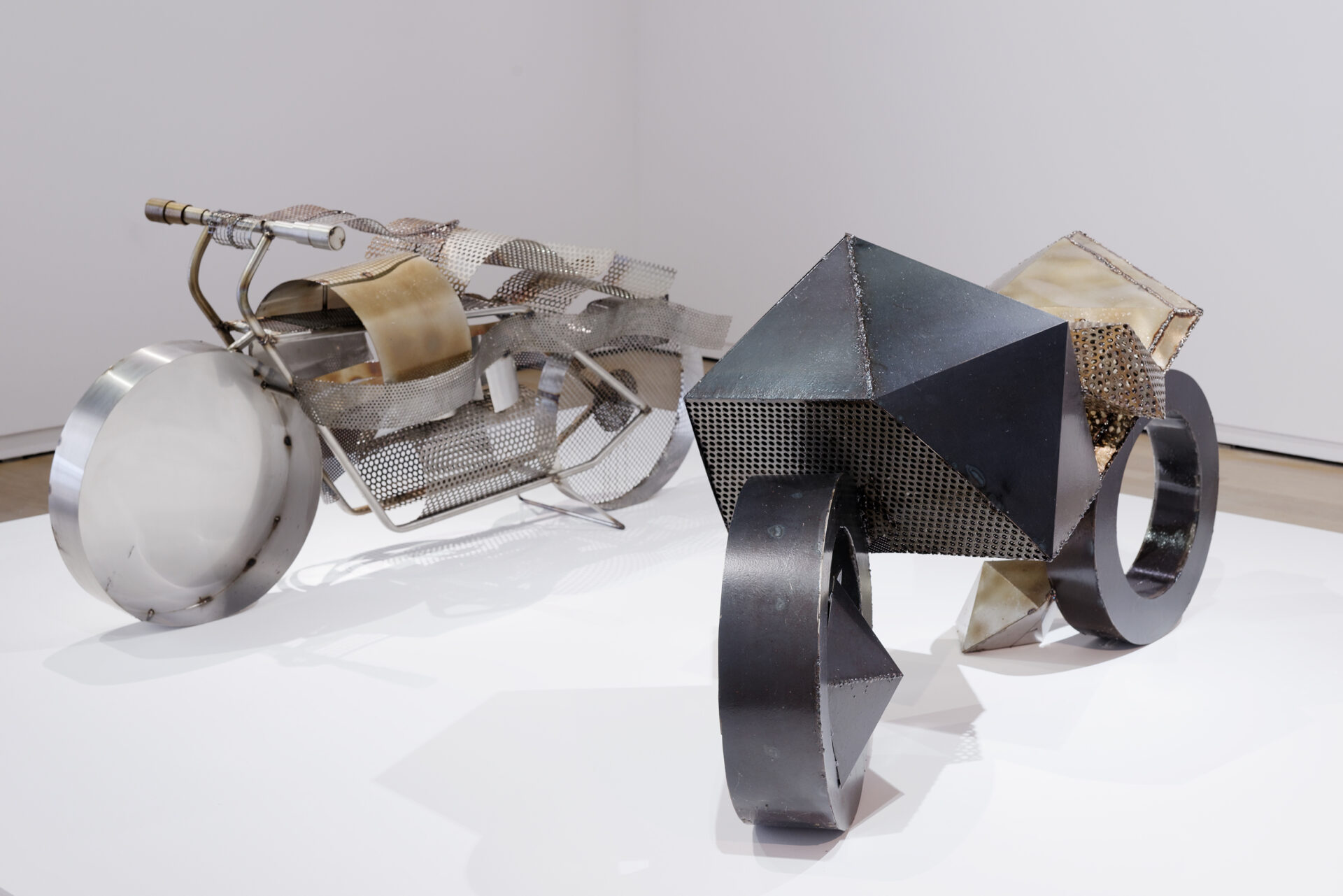

CM: The production of the door was linked to a commission: how to represent a passage between two worlds in a sculptural way, at the entrance of the Saint Sauveur train station site where the exhibition was located. Science fiction is a constant source of inspiration: these stories, these societies, these forms, these devices, linked to these futuristic tales, it’s fascinating for an artist the surpassing of reality that lays there. I was able to deal with it more specifically in the Night Engines project at the T293 gallery in Rome in 2017. I created a series of spacecrafts, and the challenge was precisely to create prototypes of spacecrafts that move away from what we all have in mind, extend this visual map, as in a video game where everything is black and new forms unveil as the game unfolds. It was one of the most difficult exercises I have ever faced in sculpture, because at the very beginning when drawing, it was impossible not to get close to known shapes. To get over that, I had to repeat each sculpture on average five times, the only way to get something new enough. I love Star Wars: The Clone Wars, where every episode you go to the planet of some of the characters, and the architecture, the costumes, the design of the environments are all different and it’s great. As an artist, I do not pretend to foresee future situations, on the other hand, my practice is crossed by the desire to try to stretch the territory, to go beyond what exists, to imagine new forms, beyond all constraints. When I was making motorcycles, it was also proposing motorcycle models without the constraint of motorization, of functioning. To be an artist is to go beyond realism, to be able to freely propose new ways to make things – and even if paradoxically I use rather conventional sculpture techniques.

The realization of In Vivo is a co-production between Pivô and the Fondation d’entreprise Ricard and has also the support of Institut Français, The General Consulate of France in São Paulo and Triangle France – Astérides.

Português

Português