In August, Pivô presents two solo shows by Colombian artists Danilo Dueñas (Cali, 1956) and Herlying Ferla (Cali, 1984), within it’s Annual Exhibition program.

Dueñas’ exhibition, will occupy Pivô’s main exhibition space, while Ferla’s will launch the instituion’s new exhibition space in the second floor. Both artists are currently working at Pivô preparing works that will be seen in Brazil for the first time.

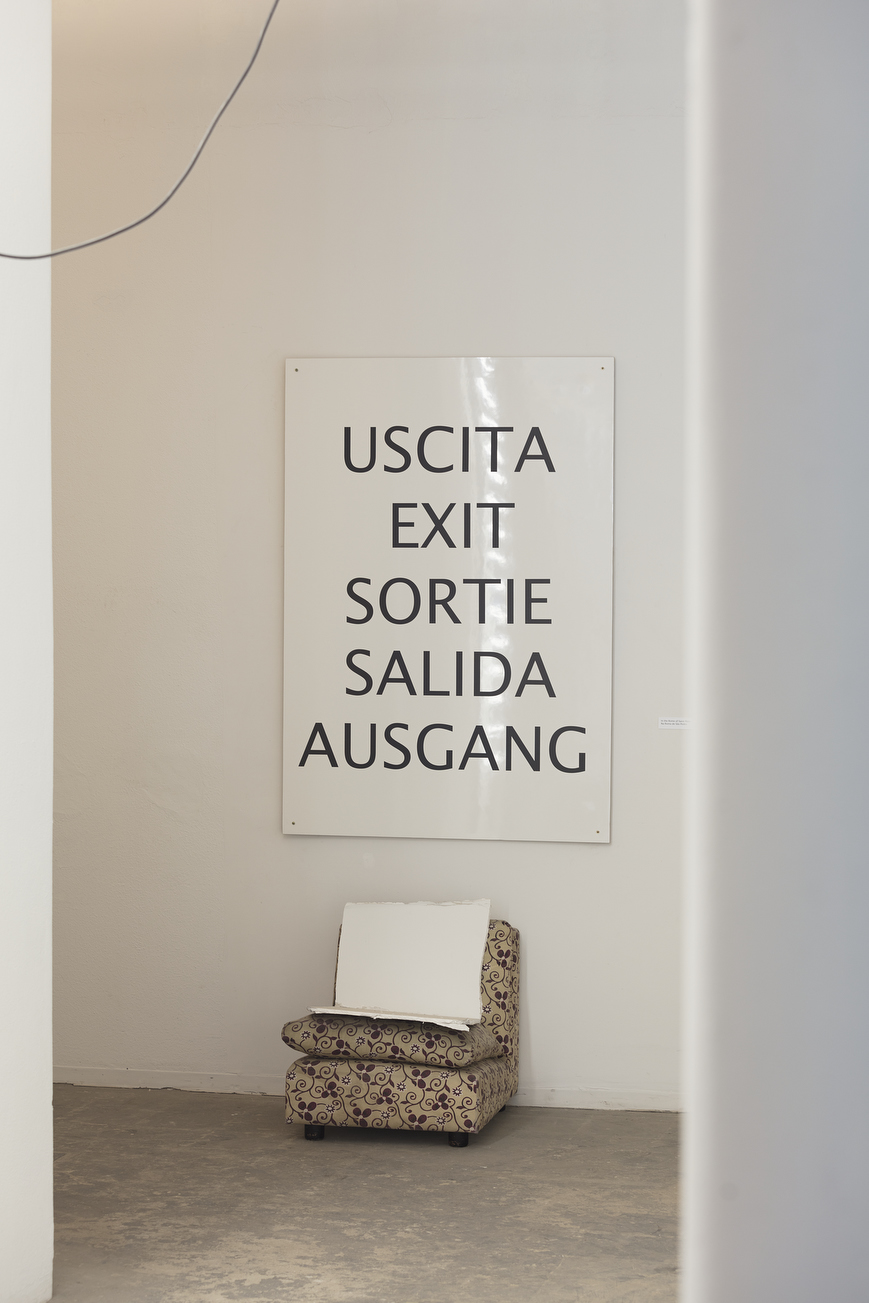

Dueñas practice departs from the selection and later a meticulous organization of found objects and discarded elements in the exhibition space. Doors, wooden and metal parts, old couches and a plethora of residual materials that lost their original function can be possible starting points for an installation. The artist has a special predilection for the obsolete, he often chooses things that lost their social function -or were replaced for a newer version of themselves – and became raw matter again.

Dueñas has a deep knowledge in art history and theory, often relying on references from this vast repertoire as sort of subtitles for these once disposed elements that gain new life through his process –the titles are a very important aspect of his practice.

Danilo Dueñas reintroduce us to what is called ‘reality’ by transforming the rhythm of the space and presenting a fresh gaze to things that are ordinary and easily overlooked. His passionate involvement with what surrounds him is extended to the public in the form of carefully balanced installations filled with an uncanny internal order.

For Pivô’s exhibition, Dueñas will produce a set of specially commissioned works departing from objects and materials storaged in Pivô’s large warehouse (the space that now houses Pivo was abandoned for over 15 years, and the institution still keeps many of the discarded materials from the previous occupations and renovations). The artist often makes an archeology of the exhibition space by searching in deposits and technical reserves of the institututions that invite him for materials, furniture and objects, mostly unused, deteriorated or forgotten, besides Pivô’s own warehouse, he will also walk around São Paulo’s central area and it’s many heaps of building’s rubble and debris.

Dueñas is also an university teacher since the 90s. He taught on Universade dos Andes. Universidade Nacional da Colombia and at Universidade de Bogotá Tadeo Lozano. This practice turned him into a major inspiration for younger generations in Colombia. Taking this into account, Pivô proposes an intergenerational dialogue between Dueñas and Ferla aiming to investigate possible correspondences between Colombian and Brazilian art scenes.

Herlyng Ferla, presents part of his recent research on opacity and transparency backed by Martinican philosopher Edouard Glissant’s writings. In a close dialogue with Danilo Dueñas , the younger artist’s work aims to relate ordinary object’s inner logic and the further transformations provoked in it by daily use. An important part of Ferla’s research is the act of gathering objects that later are slightly modified and intervened by artist, always informed by their original features.

Ferla will reedit a work that was a part of the exhibition “Geometria do Azar”, 2016, which is a composition made of cut glass pieces that resembles a tile floor and ,if looked from a distance, also can be mistaken by a wet surface. In this new version, the artist ads a newborn palm-tree, which still preserves the coconut where it came from. The image of this “seed-fruit” reminds us of what can grow out of things that can be move freely, like the coconut, that can float through the sea currents and some kinds of palm trees that came from Africa and adapted perfectly in South America.

The exhibitions are curated in partnership by PIvô’s artistic director Fernanda Brenner and Marilia Loureiro, Brazilian curator that lived in Colombia and worked in Cali. Marilia and Herlyng established a relationship in his home town that unfolded into the exhibition at Pivô. Loureiro is currently the curator of Casa do Povo, in São Paulo.

About Danilo Dueñas

Lives and works in Bogotá. Born in Cali, Colômbia

In 1999 was awarded with the Johnnie Walker Art Prize. In 2011/2012 was invited for DAAD residency program in Berlin. Participated in many international exhibitions as Beuys y más allá: El enseñar como arte at Biblioteca Luis Angel Arango in Bogotá; Correspondences: Contemporary Art from the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros at Wheaton College, Norton, EUA; Mesótica at Museu e Arte e Desenho Contemporâneo in São José, Costa Rica e Transtlantica no Museu Alejando Otero em Caracas, and the solo shows at Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Caracas (2003), Museu de Arte Moderna e Museu de Arte da Universidade Nacional (2001)

About Herlyng Ferla

Born in Cali, Colômbia, where he lives and works.

Among his recent projects are: Horas extra, MIAMI, Bogotá 2016; Acorazado Patacón, La Tabacalera, Madrid 2015; El cambio de todo lo que permanece (con La Nocturna), Pabellón Artecámara, ArtBo, Bogotá 2014; 6o Salón de Arte Bidimensional, Fundación Gilberto Alzate Avendaño, Bogotá 2014; El hueco que deja el diablo, Sala de Proyectos del Departamento de Artes, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá 2014; La desilusión de la certeza o La ilusión de la incertidumbre, Pabellón Artecámara, ArtBo, Bogotá 2013; Construcciones del deseo, Bienal Internacional de Arte SIART, La Paz 2013; Sin título (individual), Lugar A Dudas, Cali 2013; Obras apócrifas, Museo de Arte Religioso, Cali 2013; Metafísica concreta (individual), Proartes, Cali 2012; ¿Qué cosa es la verdad?, 14 Salones Regionales de Artistas, Museo La Tertulia, Cali 2012; del cuerpo (individual), Galería Jenny Vilà, Cali 2011.

About Marilia Loureiro

Born in São Paulo, where she lives and works. She knows young Colombian art scene intimately as she integrated Lugar a Dudas’s staff in Cali. She was part of the production team of the 29th Bienal de São Paulo, worked as curatorial assistant at the Museum of Modern Art of São Paulo (MAM-SP), as editorial assistant at theAteliê397 and is currently curator at Casa do Povo.

Português

Português