Recent solo exhibitions include Lua Cão (with João Maria Gusmão + Pedro Paiva), a project initiated in 2017 by Galeria Zé Dos Bois in Lisbon, that traveled to the Kunstverein München, and conclude at La Casa Encendida in Madrid in 2018; Knife in the Water, 2018, at Travesía Cuatro, Madrid; Ouro Mouro, 2018, at the Quetzal Art Centre, Vidigueira, Portugal; Baklite, 2017, at CAV Centro de Artes Visuais, Coimbra, Portugal; Cápsulas de silencio, 2016, within the Fisuras Program, at the Reina Sofia Museum, Madrid; Roda Lume, 2016, at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Antwerp, M HKA, Belgium; Meio Concreto, 2013, at Museu Serralves in Porto, Portugal; Um homem entre quatro paredes, 2013, at the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, Brazil; The Sunspot Circle, 2013, at The Flat Time House, London, UK, among others.

The artist has also participated in numerous group shows in institutions and biennales such as: Anozero – Bienal de Arte Contemporânea de Coimbra, 2017, curated by Luíza Teixeira da Freitas; L’exposition d’un Rêve, 2017, at Gulbenkian Foundation Paris, ACMI Melbourne and TATE Modern, a project by Mathieu Copeland; Hallucinations, Documenta 14, 2017, Athens, a festival curated by Ben Russel, among others.

Pivô is pleased to present Volta Grande, Portuguese artist Alexandre Estrela’s first solo show in Brazil, curated by Luiza Teixeira de Freitas. The exhibition shows of 7 works from which 6 are entirely new. Drawing its title from the name of a small town in the Brazilian interior state of Minas Gerais, Volta Grande’s history is that of being the birth and death place of Humberto Mauro (1897-1983), deemed by some to be the “father” of Brazilian cinema.

According to the curator, “Volta Grande” gathers in the curved base of the Copan building a body of work that is the result of dead hours and concentric walks that Estrela made around a house. Matter and memory are the guiding threads of this exhibition that intertwines time and body, video and sculpture. There is something in these works that resonates to infinity, as the image exists beyond the image in the dialog that it establishes with the surfaces of projection.”

Estrela, who works mainly with video and photography, inspects the relationship between matter, images, and perception. His works present landscapes and images of nature through different technologies, discussing the canons of modern art history as well as studies about behaviorism, physics, and acoustics amongst other sciences. Time and perception; factual and fictional history; memory and materiality are central subjects of the show.

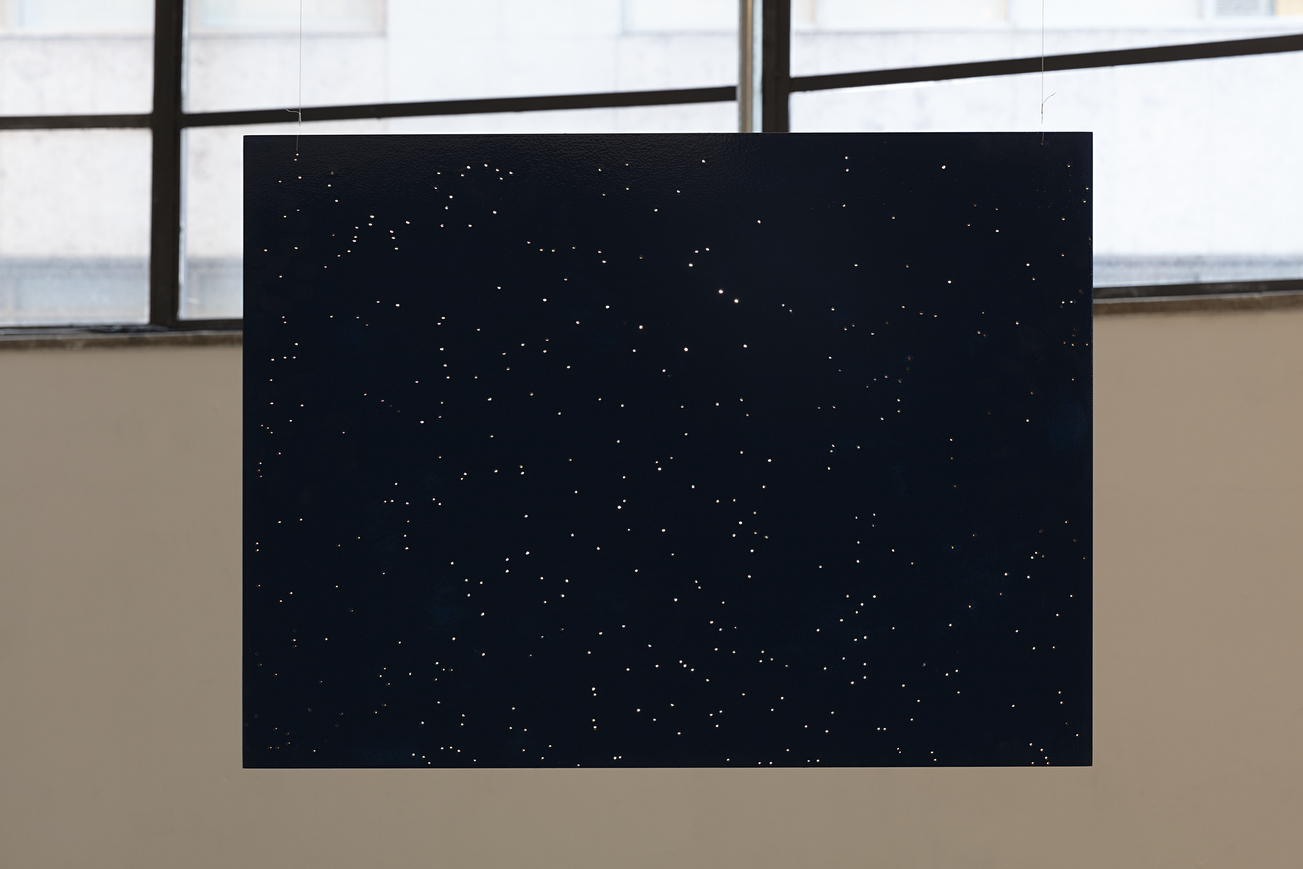

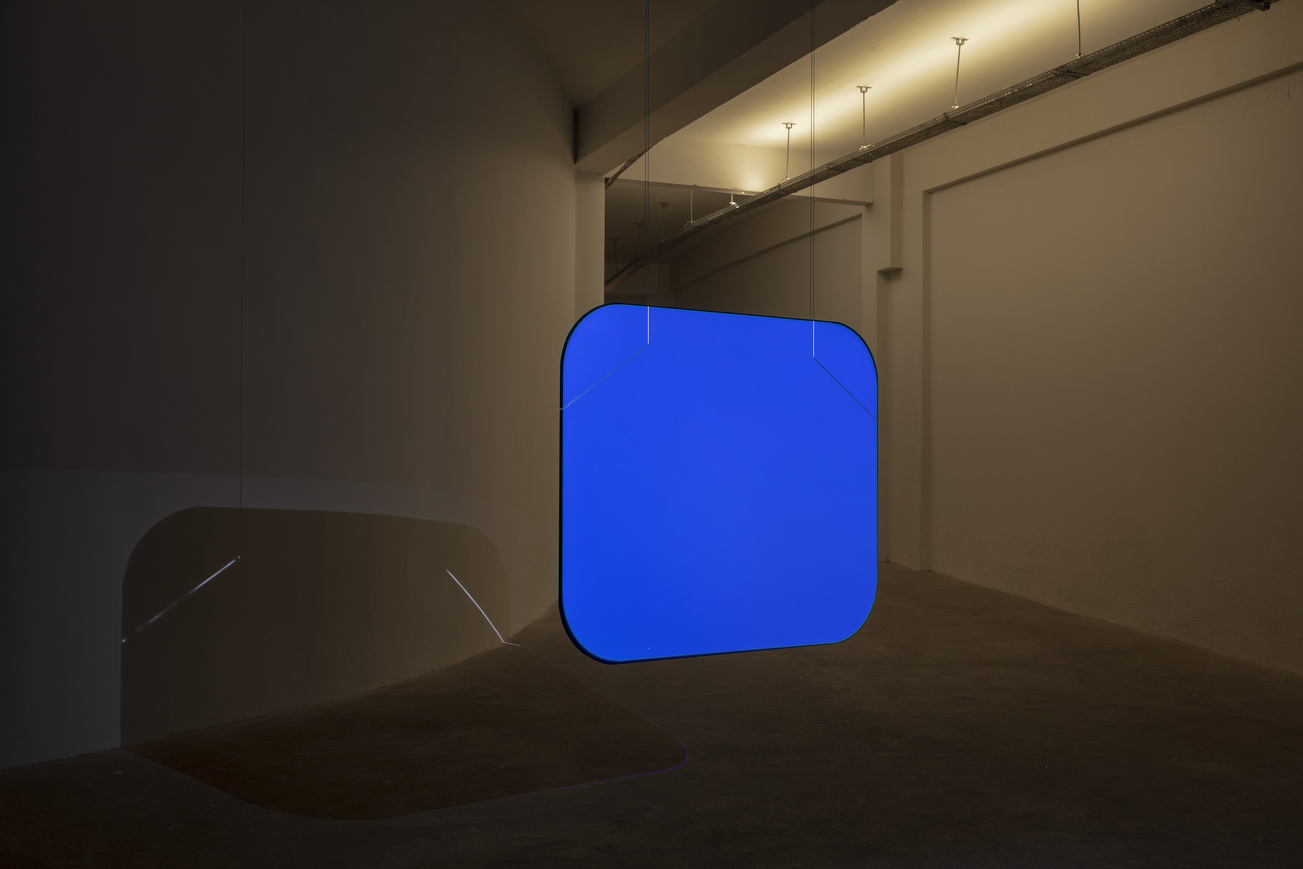

The work Águas de Março (2019) shows a soaked piece of tropical cedar filmed drying in the sun on one of the hottest days ever recorded in Minas Gerais. The camera could not withstand the torrid heat and stopped filming within seconds of the wood finally drying. The image of the wood is projected onto a woodchip board, to which it bonds like a skin, alternately drying and growing moist in an eternal cycle. Another piece, entitled Cupim (2019) shows the image of a tropical wood devoured by termites projected onto a wooden screen. The holes made by the insects coinciding with the holes made in the wood. The back of the screen, painted blue reveals a constellation. Volta Grande (2019) is a photograph of a trunk of a pau mulato tree projected onto a cylinder placed in front of a vertical plane. The tube incorporates the image of the tree and the smooth bark becomes one with its surface. An imperceptible rotation of the tube reveals a horizontal line that draws its outline.

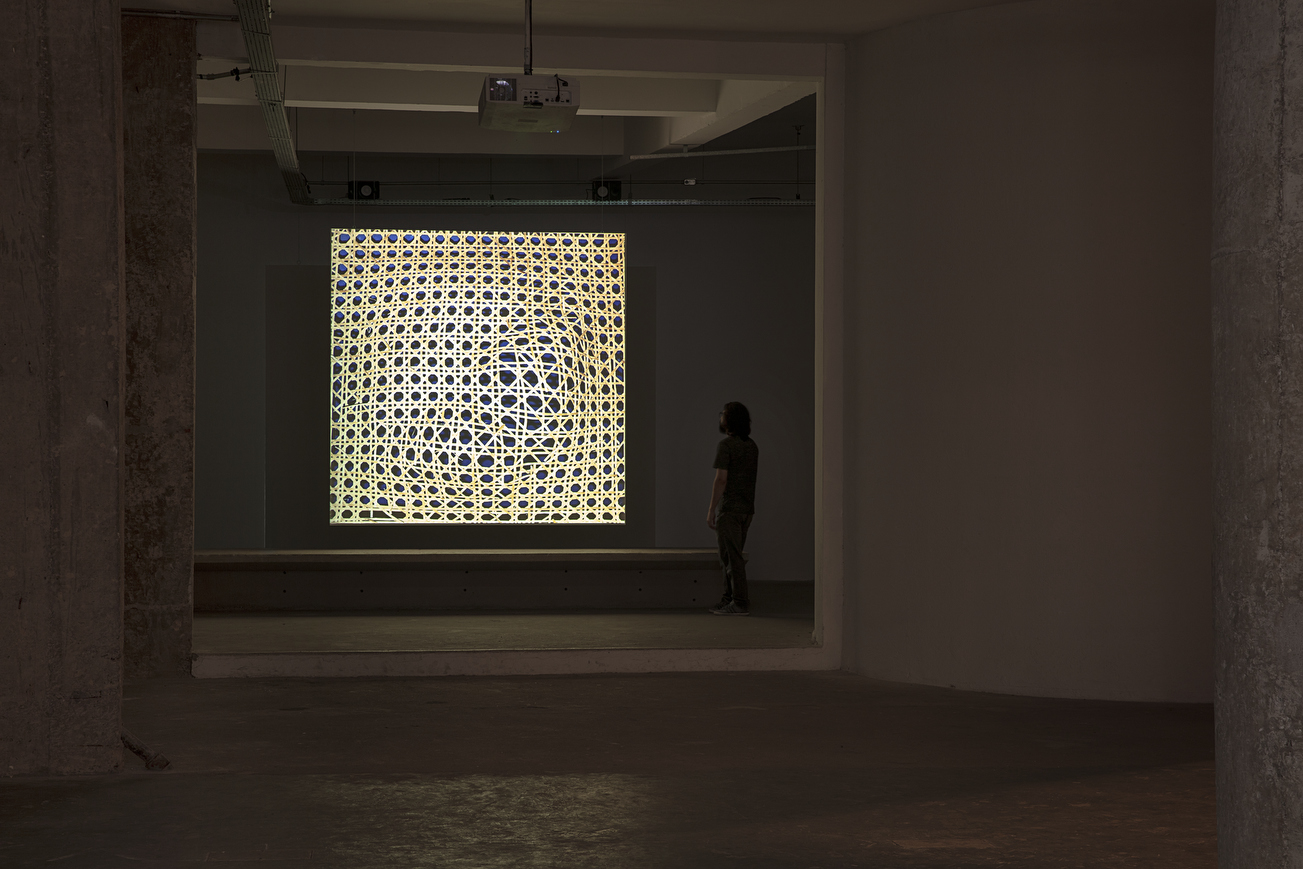

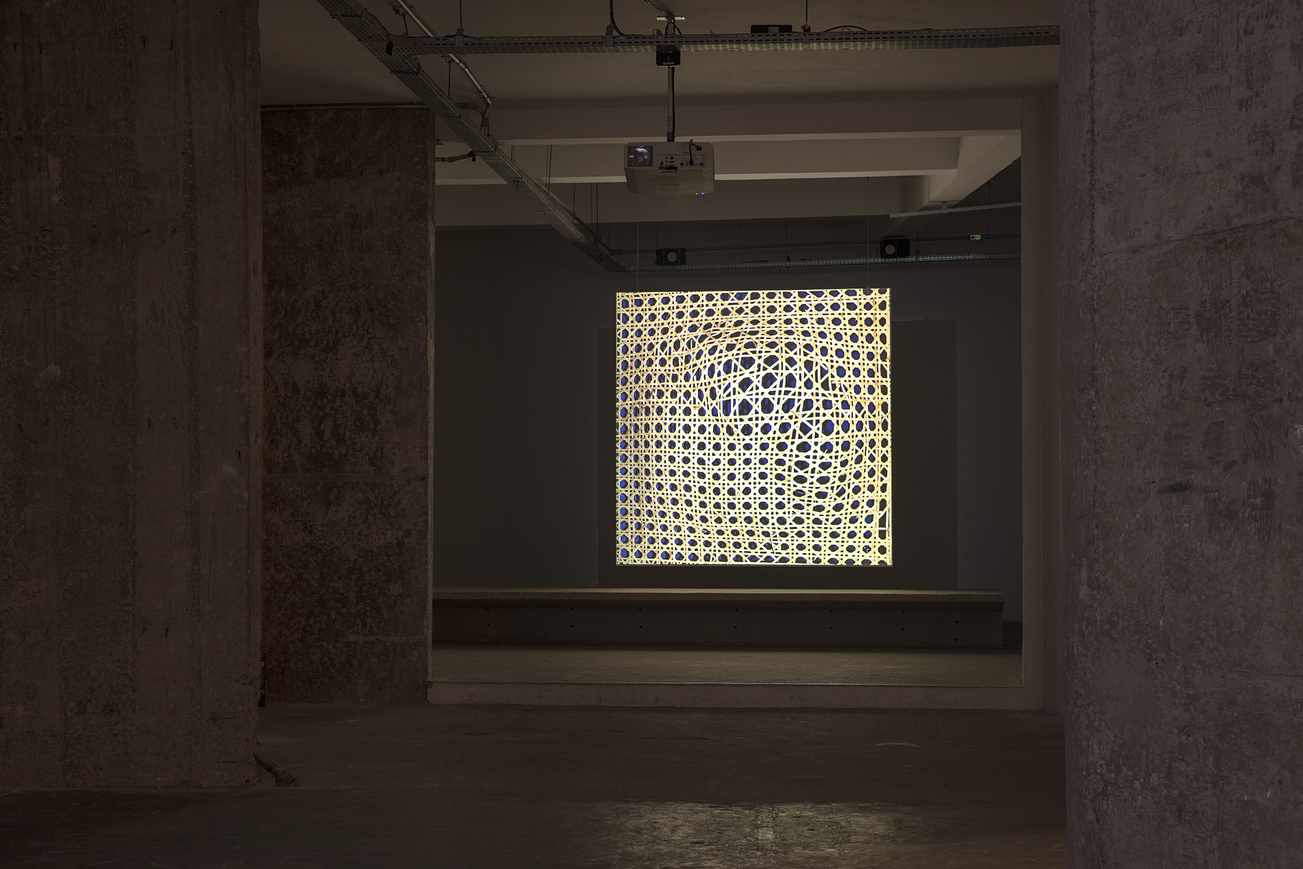

The work, A Cadeira de H.M. (2019) is a piece in which Estrela refers directly to Humberto Mauro. It shows an image of a deformed seat of a chair caned by Mauro, animated with the sound of his voice. Appealing to future generations of Brazilian cinema: “I have great esteem for the youth of Brazil and have great belief in their abilities. My hope is for young filmmakers to produce truly great works of cinema so that Brazil has an ever better tomorrow.” At the end of his life, Mauro, for some the father of Brazilian cinema dedicated himself to the practice of Brazilian straw craft and the study of Amerindian language, Tupi. Mauro believed that cinema, just like Tupi, was a language that needed a structure in order to avoid extinction.

Português

Português