Ana Vaz (1986, Brasília) is an artist and filmmaker. Her film-poems walk along territories and events haunted by the impacts of colonialism and their imprint on land, human and other-than-human forms of life. Expansions or consequences of her films, her practice may also be embodied in writing, critical pedagogy, installations, film programs or ephemeral events.

Her films were presented and discussed at film festivals, seminars and institutions such as the Berlinale Forum Expanded, New York Film Festival, TIFF Wavelengths, Cinéma du Réel, CPH: DOX, Flaherty Seminar, Tate Modern, Palais de Tokyo, Jeu de Paume, LUX Moving Images, Courtisane, among others. Recent exhibitions of her work include: “Penumbra” at Complesso dell’Ospedaletto (Venice); “Il fait nuit en Amérique ” at Jeu de Paume (Paris, France); 36th Panorama of Brazilian Art “Sertão” at MAM (São Paulo), “Meta-Arquivo 1964-1985: Space for Listening and Reading Dictatorship Stories” at Sesc-Belenzinho (São Paulo), Profundidad de Campo no Matadero (Madrid, Spain) and “The Voyage Out” at LUX Moving Images (London). In 2015, she received the Kazuko Trust Award from the Film Society of Lincoln Center in recognition of the artistic excellence and innovation of her work in moving image. In 2019, she received support from the Sundance Documentary Film Fund to complete her first feature film. She is a member and founder of the collective COYOTE, along with Tristan Bera, Nuno da Luz, Elida Hoëg and Clémence Seurat, an interdisciplinary group that works in the fields of ecology and political science through experimental forms (conversations, drifts, publications, events and performances).

https://vimeo.com/anavaz

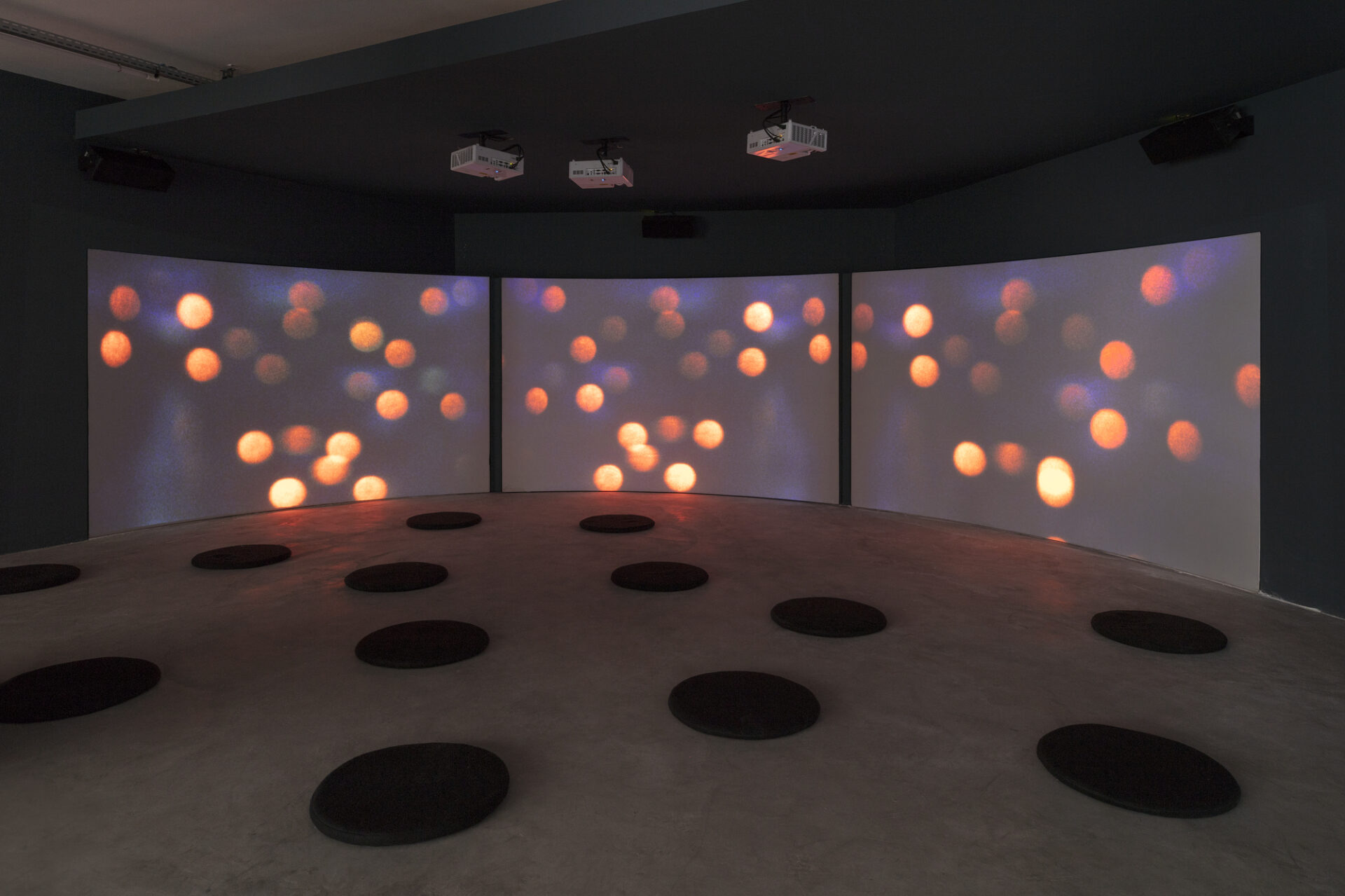

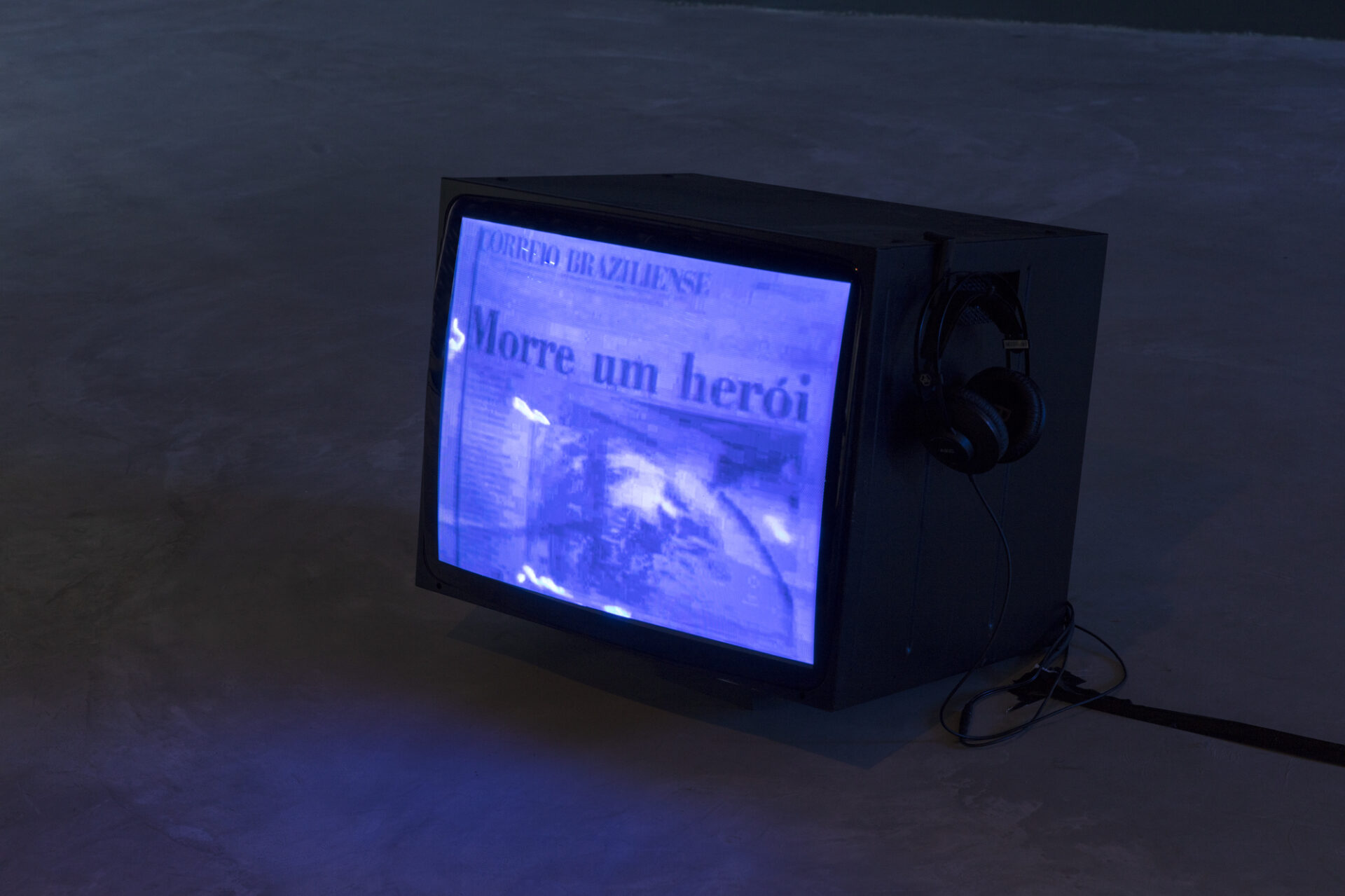

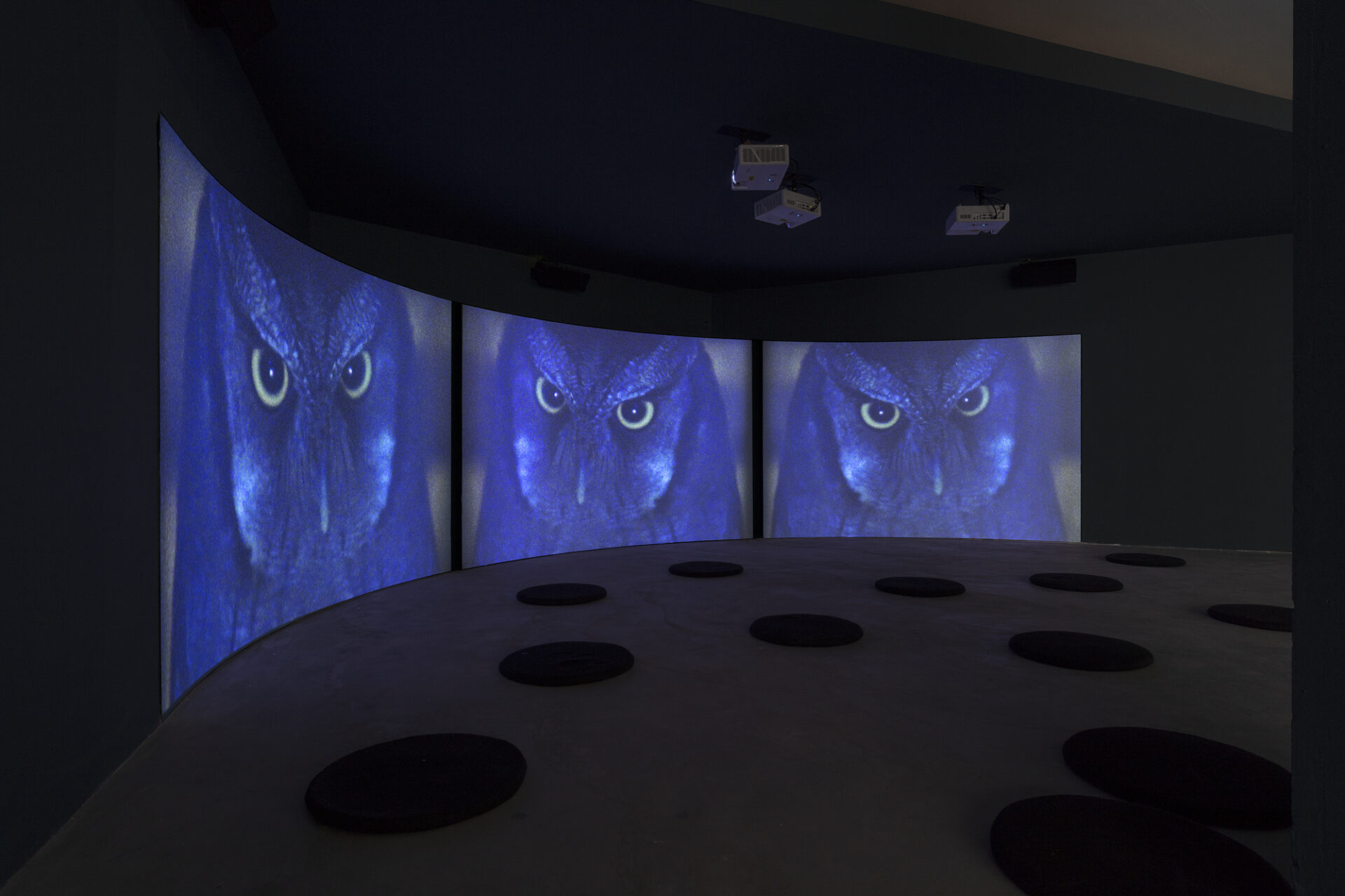

Originally planned for 2021, the exhibition by artist Ana Vaz was one of the projects crossed by a significant time dilation in its production process. The exhibition, now on show at Pivô, entitled É NOITE NA AMÉRICA [IT’S NIGHT IN AMERICA], brings, besides other works, an instalative version of the homonymous film directed by the artist, exhibited at the Locarno Festival, in 2022, and that received a special mention in the Pardo Verde, an award dedicated to films with an environmental theme.

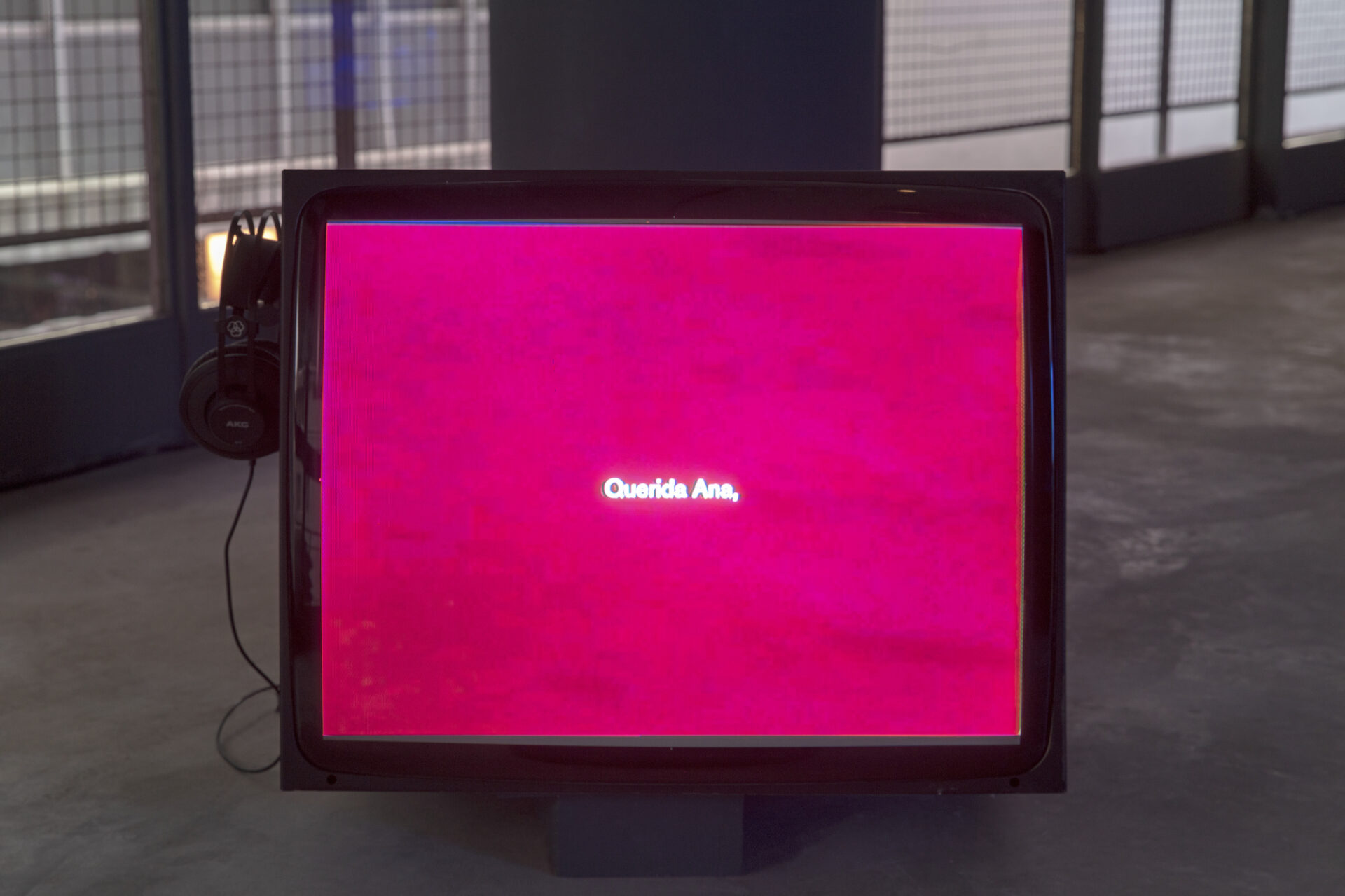

An eco-terror tale freely inspired by the reading of the book A cosmopolitics of animals, by Brazilian philosopher Juliana Fausto, ‘É NOITE NA AMÉRICA’ follows the paths and detours of wild animals, fugitives from the destruction of the Brazilian cerrado in the middle of modern Brasília. In this book, adapted from her doctoral thesis, Juliana Fausto investigates, from a philosophical point of view, the political life of non-human beings and questions the idea of the exceptionality of the human species. After reading the book, Juliana Fausto and Ana Vaz began a dialogue and an exchange of correspondence – part of which was, in 2021, published in Pivô Magazine #2.

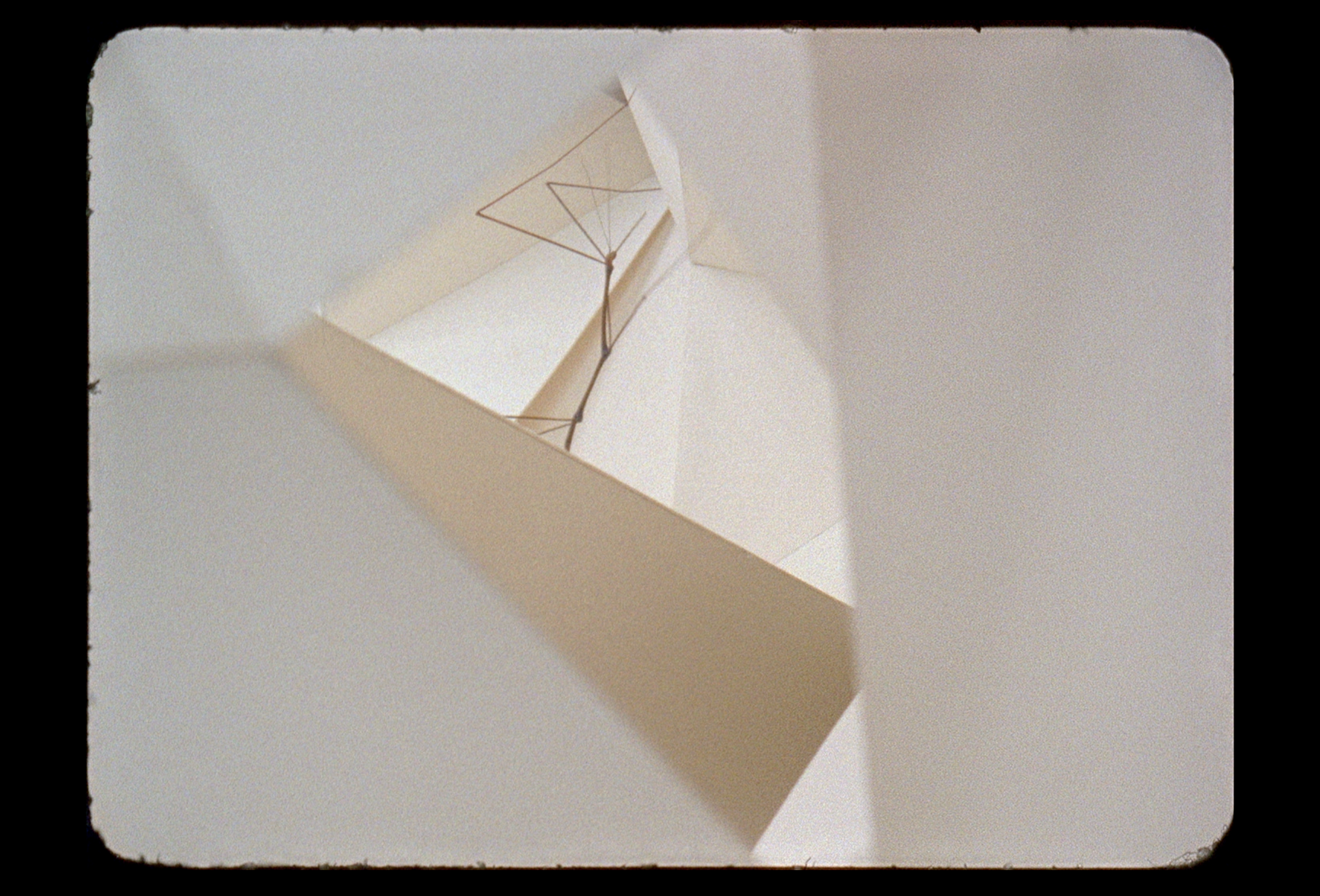

Shot entirely on expired 16mm film reels and with the cinematic technique of American night (day for night), the film narrates the grim plot of the arrival and survival of this fleeing fauna in search of refuge on a “planet with many refugees and few refuges”, in the words of Juliana Fausto quoting Anna Tsing.

For the soundtrack of this eco-terror, Vaz uses the composition Panthera Onca by Guilherme Vaz, her father, multimedia artist and composer. In the film, the spectator is provoked to reflect the visible and subjective effects of colonialism on different bodies, territories and species. In an experimental and non-linear approach, we witness stories and experiences such as that of Macau, a giant otter born in Dortmund in Germany and transferred to Brasilia zoo in order to “repopulate the land of its ancestors”, in the artist’s words.

The installation ‘IT’S NIGHT IN AMERICA’ is a commission and production by Fondazione In Between Art Film, with co-production by Ana Vaz, Spectre Productions and Pivô with additional support from Jeu de Paume, Paris.

Ana Vaz is one of the most relevant contemporary artists and filmmakers, having her films and exhibitions circulated through several museums, festivals and film libraries. Her work is noticiable by a constant experimental challenge on the poetic forms of contemporary cinema, highlighting the profound contradictions of our time, and questioning, above all, the destructive practices of the colonial modernity.

Service:

Ana Vaz: É NOITE NA AMÉRICA [IT’S NIGHT IN AMERICA]

Curator: Fernanda Brenner

Exhibition period: 03/09/2022 to 06/11/2022

Wednesday to Sunday, from 12 pm to 18 pm

Opening: 03/09/2022, at 1pm

Free entry

Português

Português